By Elizabeth Hoover | Fall 2021

Photography by Laura E. Partain

As an academically gifted second grader in Louisville, Ky., Renã Robinson (Ph.D. '07, Chemistry) was bused from the all-Black school in her neighborhood to a mostly white one. There she saw stark differences in the quality of books, supplies, and even instruction. That bothered her. So, with her mother’s encouragement, she wrote to the school superintendent.

“My mom is a very honest person who calls out things as they are,” she explains. “When things weren’t as they should be, she’d help us find a way to navigate that.”

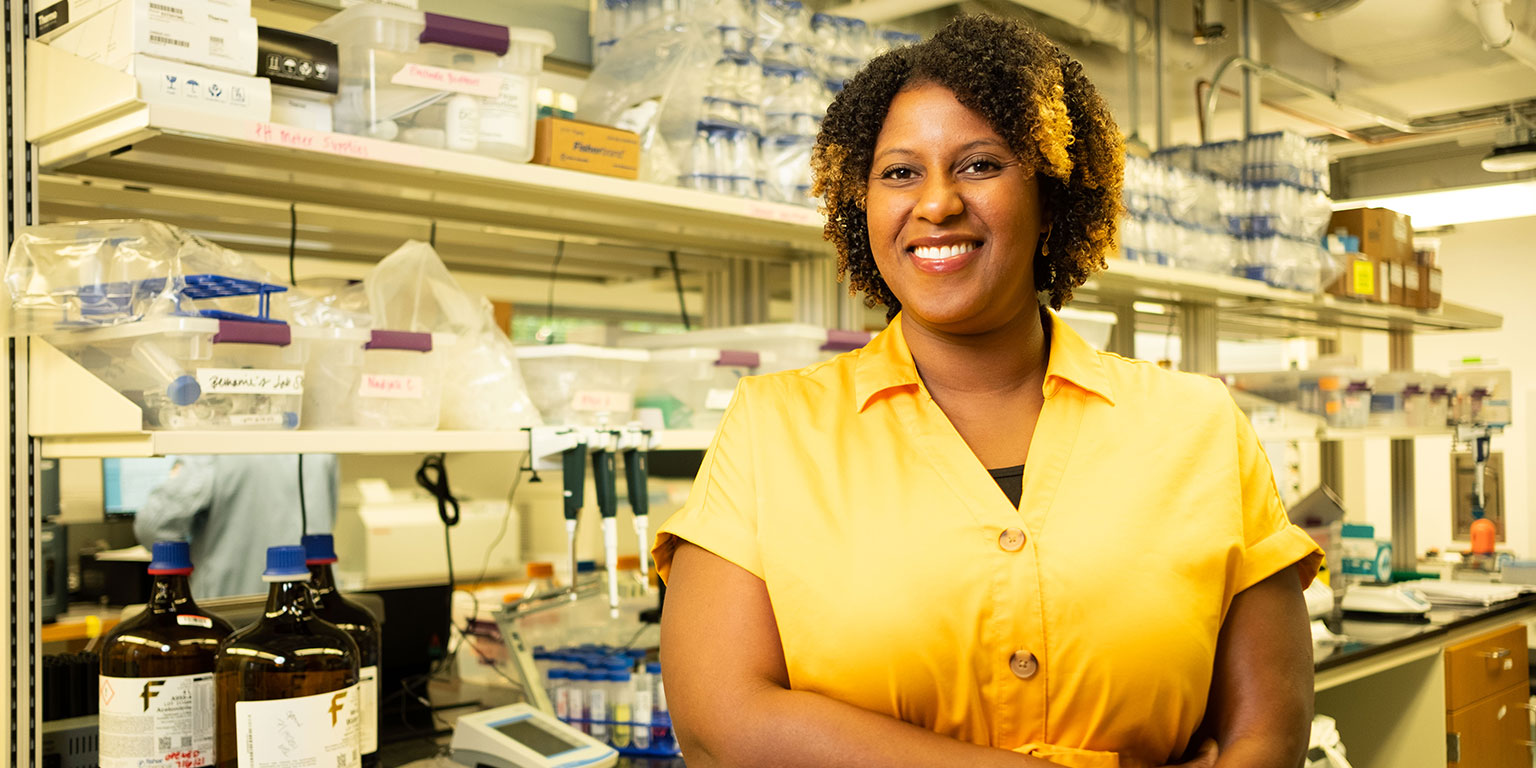

Now, as the Dorothy J. Wingfield Phillips Chancellor’s Faculty Fellow and principal investigator at a pioneering chemistry lab at Vanderbilt University, Robinson (née Sowell) continues to be committed to addressing racial disparities, not only in her research, but as a mentor and advocate for young scientists.

“It’s extremely important to have a diverse team in a lab,” she says. “If we’re going to move the world’s greatest problems forward, all the different voices we have in our society must be represented.”

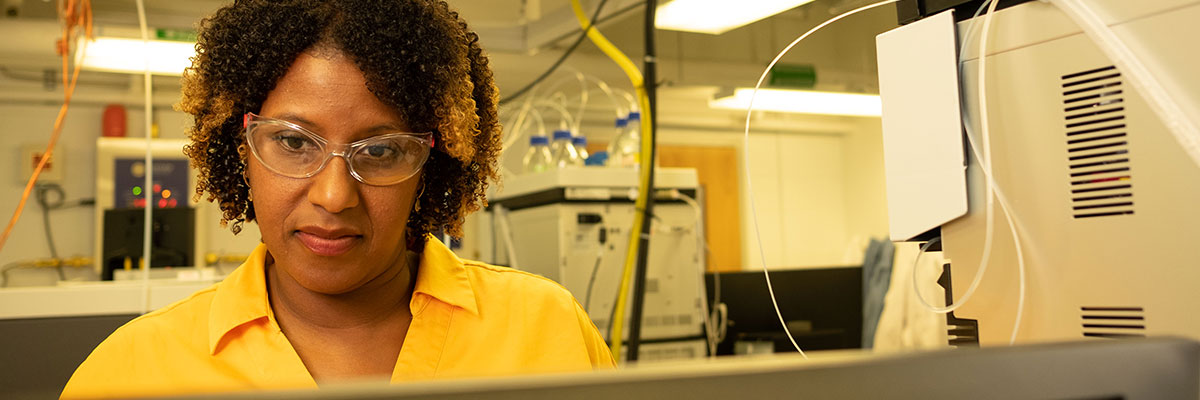

The problem Robinson’s lab focuses on is aging, specifically the role that proteins play in triggering and indicating conditions including Alzheimer’s Disease, sepsis, and the weakening of the immune system. In order to do this work, Robinson first needed to develop innovative techniques in mass spectrometry and proteomics, or the analysis of complete sets of proteins within a group of cells or organ. Her lab is using these techniques to try to pinpoint why African Americans are twice as likely as white people to contract Alzheimer’s and sepsis, among other projects. This is a complex, interdisciplinary question considering environmental factors, stress levels, and related conditions like hypertension and diabetes.

“Stress can lead to premature biologic aging,” Robinson explains. “Who you are matters in terms of the stress you experience on a daily basis.”