By Susan M. Brackney | Fall 2021

Photography by Anna Powell Denton and IU Studios

“I think everybody kind of gulped a little bit when we got the charge to begin to work on this,” Jeff Zaleski admits. “You realized right away the magnitude — knowing how many students are on campus, knowing the gravity of the situation, the severity of the hospitalizations, and what hospital volume we actually have here in Bloomington. We realized quickly how important and significant it could be to do this well.”

The task? Set up a COVID-19 testing lab on the IU Bloomington campus — and get it done as quickly as possible.

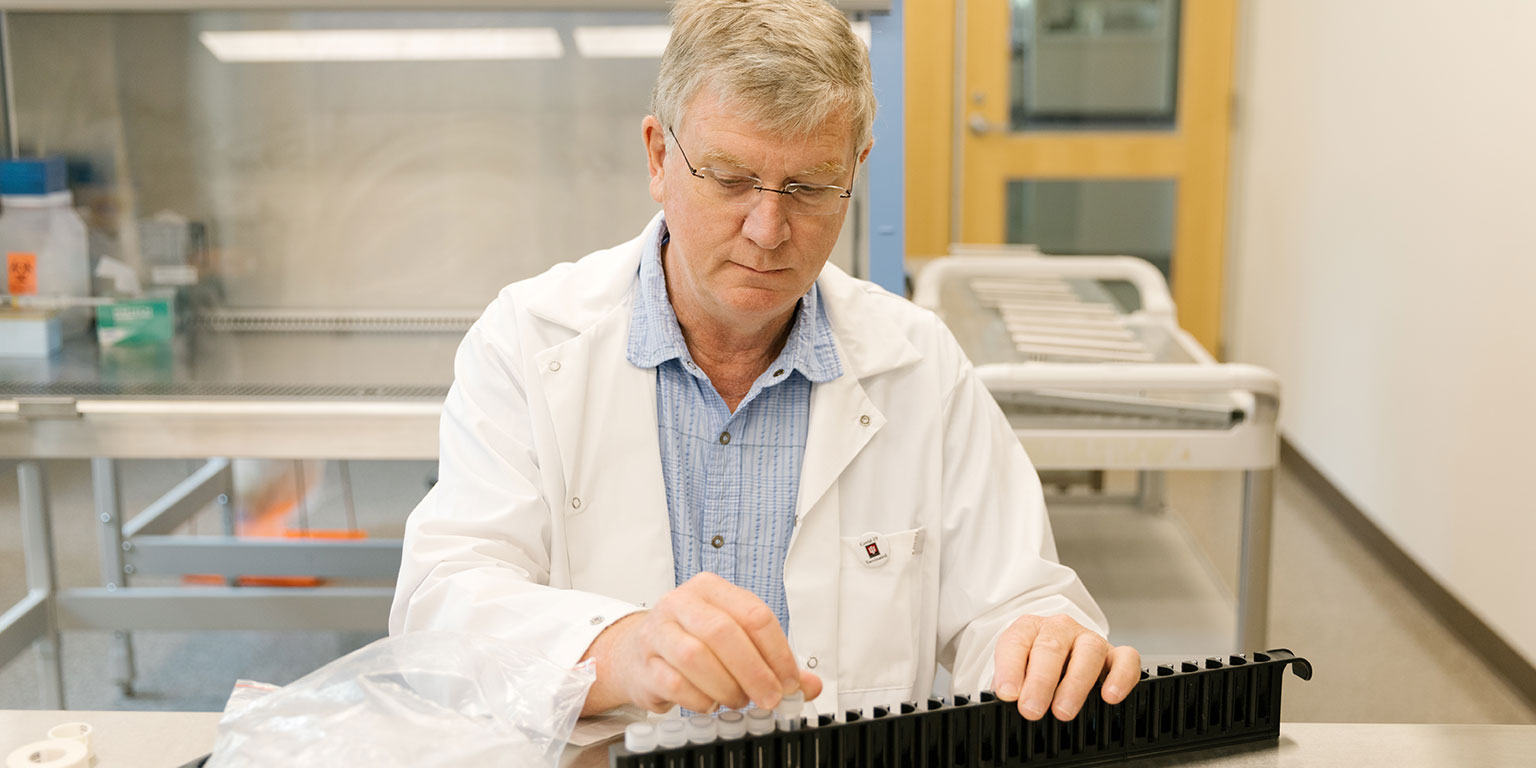

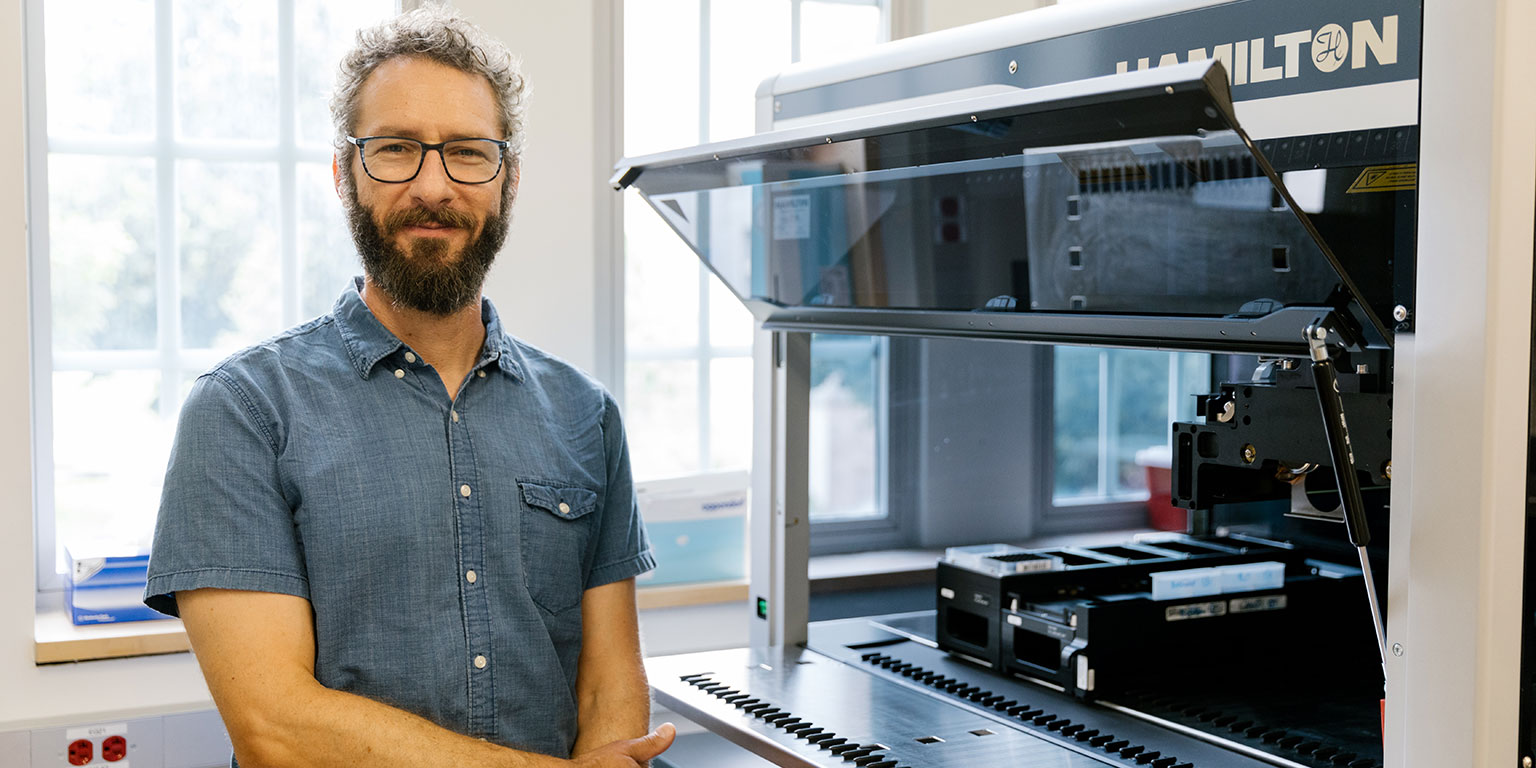

Zaleski is interim vice provost for research and associate vice provost for sciences, in addition to serving as a provost professor in the College of Arts and Sciences’ Department of Chemistry. “There was pressure, as the calendar was moving toward the spring semester, to get [IU’s testing] volume up to something like 50,000 samples a week,” Zaleski notes.

IU implemented random COVID-19 testing in August 2020, but officials were relying on an outside lab to turn around approximately 15,000 tests each week.

“Those tests cost 10 times more than when we do it in-house, and it typically took two or three days to get the results back,” says the College’s Executive Dean Rick Van Kooten. “If somebody is tested and they’re positive and they’re walking around not knowing they’re positive for two or three more days, that really exacerbates the spread.”

In fact, those extra days could be deadly. Zaleski began assembling the team.

Lab work

“Craig Pikaard was one of the first ones to look into the actual type of test from the [scientific] literature,” Zaleski says. “He was convinced that we could pull this off from a biochemistry point of view.”

Pikaard is a distinguished professor and the Carlos O. Miller Professor of Plant Growth and Development in the College’s Departments of Biology and Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. He’s also an investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. In lieu of the brain-tickling nasopharyngeal swab test, Pikaard’s team devised the implementation of a newer, saliva-based method of testing. The U.S. reported its first COVID-19 death in February 2020 and, one month later, the World Health Organization officially declared COVID-19 a pandemic. In April, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration authorized the use of saliva-based COVID-19 testing on an emergency basis.