By Raymond Fleischmann | Summer 2019

All of a sudden, everyone is a photographer. Cell phones have become a central necessity of modern life, and cameras have managed to tag along. We take photos of our food. Our drinks. Our nights on the town. We take photos of our kids, and we take photos of ourselves — so many photos of ourselves — the desire to take photographs and to be in photographs more prevalent, it seems, than ever before.

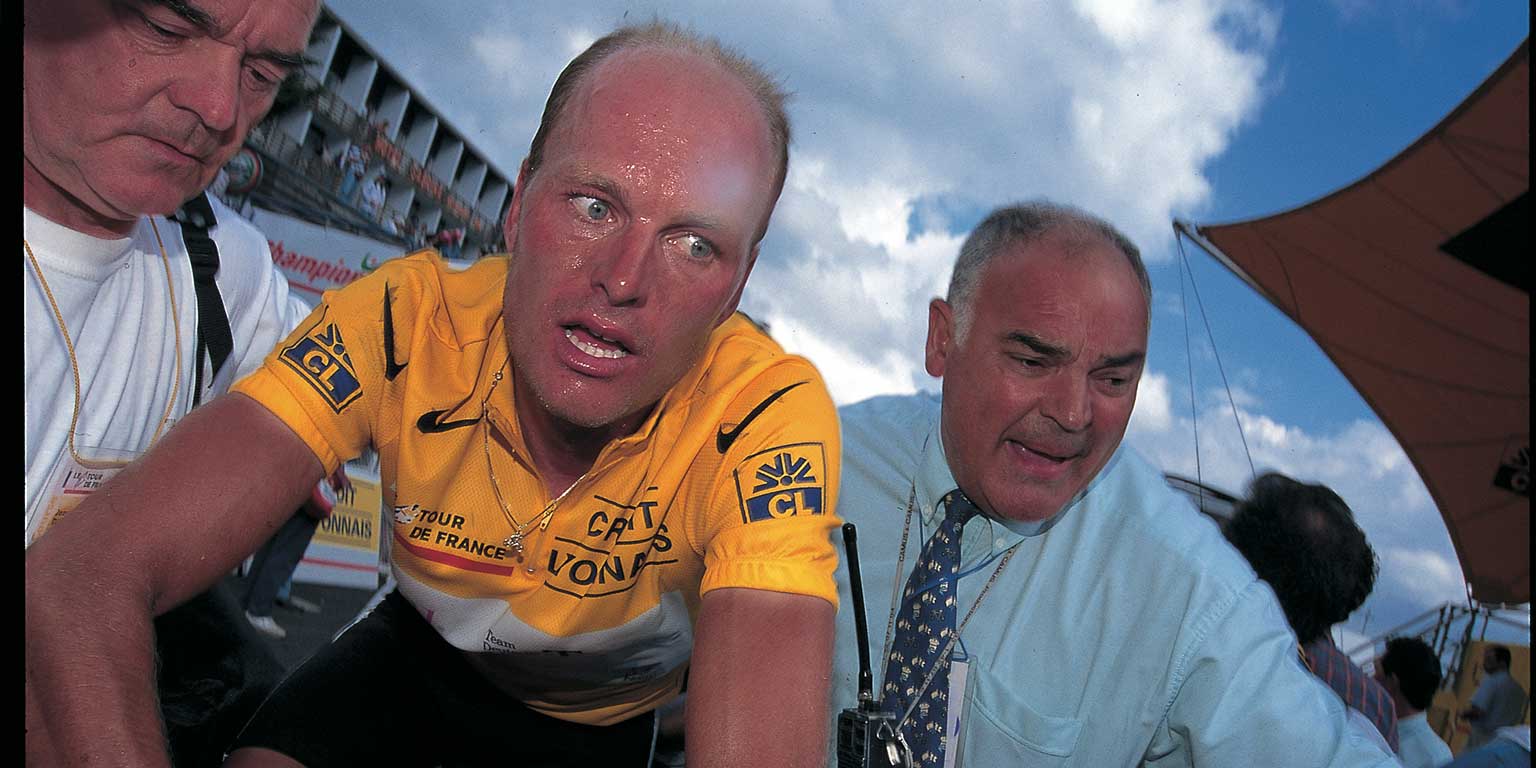

But there’s a big difference between taking pictures and taking good pictures. Just ask James Startt (M.A. ’92, Art History), a guy who’s dedicated the larger part of his life to the art of photography. Although Startt was born in the United States, he’s been based in Paris since the 1990s, and throughout the past 30 years he’s established himself as one of the preeminent names in street, sports, and documentary photography. He’s especially well-known for his photos of the annual Tour de France, and his work has been displayed in galleries, magazines, and books all over the world.

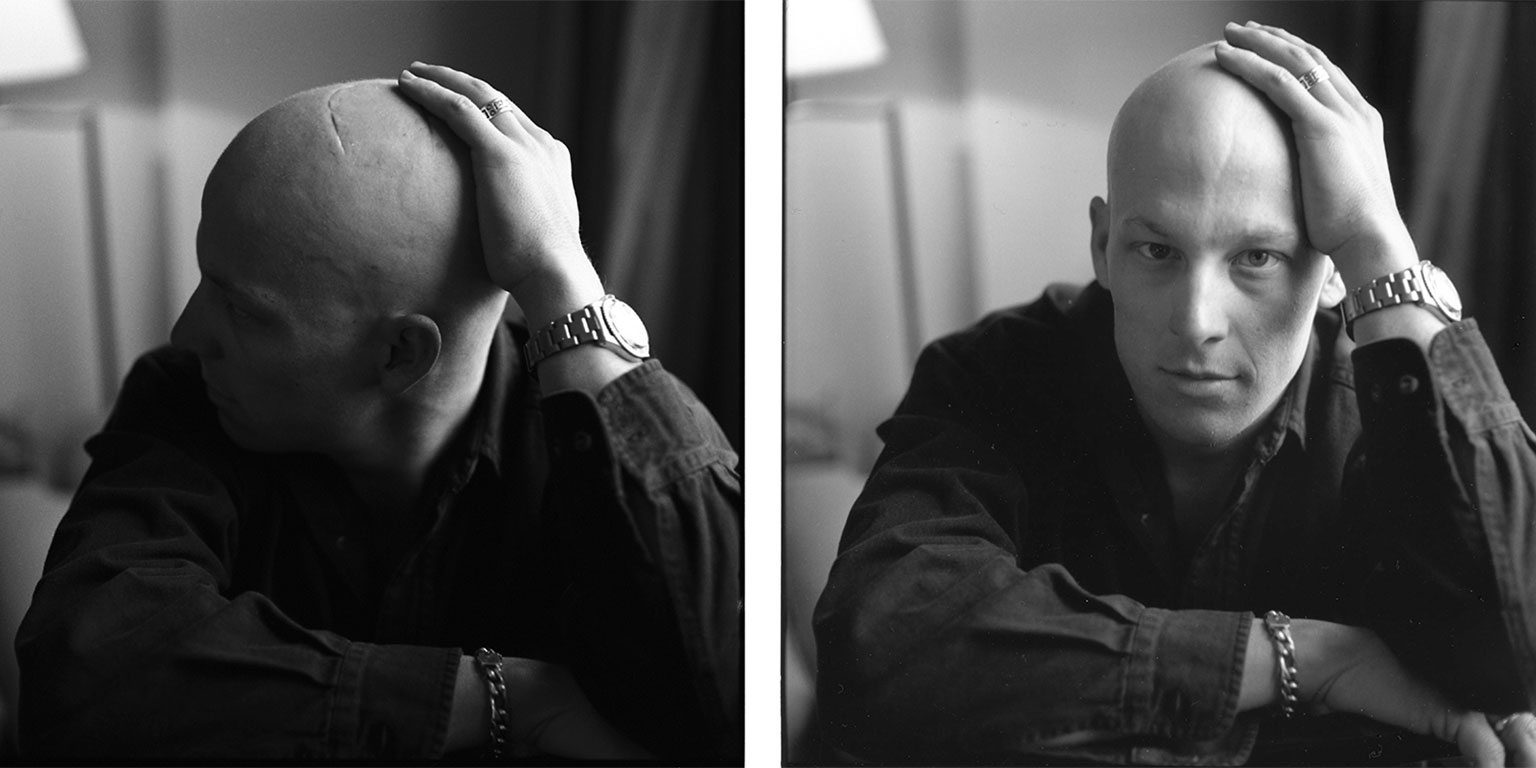

On the day of our interview, Startt wears a bowler hat and black, plastic-framed glasses. He sports a peppery goatee that he occasionally touches as he speaks, thinking over a question of mine or recalling what type of camera he used for a certain shoot. Startt is soft-spoken, thoughtful, measured. He travels constantly — he arrived in Chicago from France just a few days before — and it’s as if he revels in the few moments of stillness that our interview provides.

And that makes sense. Stillness, after all, is his job. His art form. He’s a master of capturing emotions in time, of trapping singular moments that tell entire stories. He’s a pleasure to talk to, relaxed and affable, and even in answering my questions his talents as a photographer are apparent. His responses are thorough and highly specific — he remembers places and people remarkably well — and as we chat it’s easy for me to imagine entire scenes and settings. He’s got a knack for details.

Raymond Fleischmann: What’s your earliest memory of photography? Do you remember the first photograph that you ever took?

James Startt: Yes, I do. Very much so. My father was a professor at Valparaiso, so I was a faculty brat, but the advantage of that was that we had sabbaticals sometimes. We were over in England one year, and I think it was a Kodak Brownie that my mom had, but we were visiting Cambridge or Oxford and I took my first picture there. I remember that because for years, my mom had two photo albums from our two trips overseas — one from England and one from Ireland — and she had that in there. You know, “Jimmy’s first picture.”

Fleischmann: How old were you?

Startt: I was in third grade. So, about nine or ten. I always thought cameras were cool, like bikes or guitars, all the objects that still resonate with me. I went to undergraduate at a small school out east, which is now called McDaniel College. It’s a very small liberal arts college, and one January term they offered photography, which was my first chance to really do it. [A few months before that], I had moved to New York City for the summer, and I was a bicycle messenger, and the first thing that happened to me was that my bicycle got stolen. But my parents’ insurance was very reliable, and it gave me $200, which was just enough for a Canon AE-1. [Laughs] For my whole life, it’s always been between bikes, photography, and music. So anyway, then I had that photography class, and for three or four weeks I was just taking pictures all day and going to the darkroom, and that was my first real hands-on approach to learning what picture-taking was all about. I remember just losing track of time in the darkroom. You know, turning on the Talking Heads and just getting lost. So, I knew that there was some real love there.