"Research Spotlight" is a new feature from The College magazine, which highlights recently published peer-reviewed work by notable alumni and faculty of the IU College of Arts and Sciences.

By Mark McGarvie | June 2024

Reprinted with permission of New York Archives Magazine

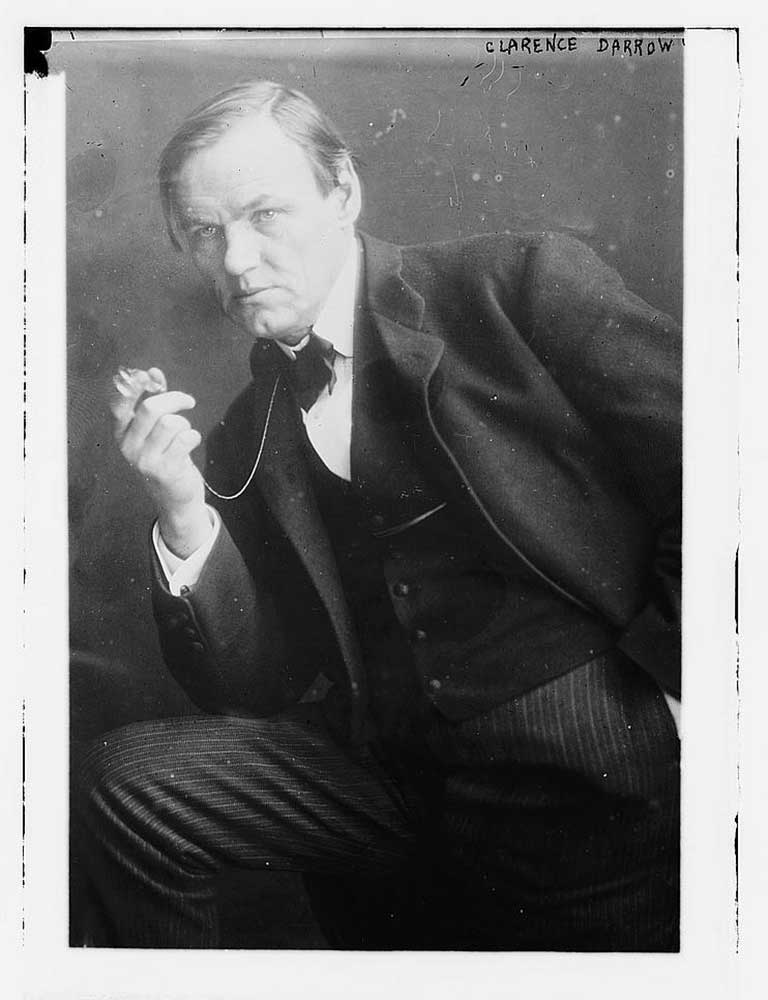

It is unfortunate, if not surprising, that historians have often considered Mary Field Parton most notable as the mistress of famous attorney, Clarence Darrow. Parton (1878–1969) came of age and rose to prominence at a time during which society defined women by their roles relative to men. But Parton contributed significantly to the reform initiatives of the early 1900s, working in settlement houses, as an author of magazine articles and books, as a leading exponent of organized labor, and as a crusader for women’s rights—especially sexual freedom. As such, she provides a case study in the feminist ideal known as the “new woman.”

Parton came to New York in 1909 from Chicago at the age of 31. She had already had affairs not only with Darrow, but also with well-known play- boys, prominent journalists, the president of the University of Chicago, the city police inspector, and a Russian diplomat. In response to both a need to distance herself from Darrow and his wife and to find a pursuit more significant to her than settlement work, she assumed a writer’s position in Manhattan for Darrow’s friend, Theodore Dreiser. Dreiser had achieved some fame as an author for his novel Sister Carrie, published in 1900. By 1909, he had become the editor of The Delineator magazine. He hired Parton to write human-interest stories on immigrants, workers trying to unionize, and women unable to support themselves because of societal restrictions. Parton also continued her work for sexual freedom.

Free Love

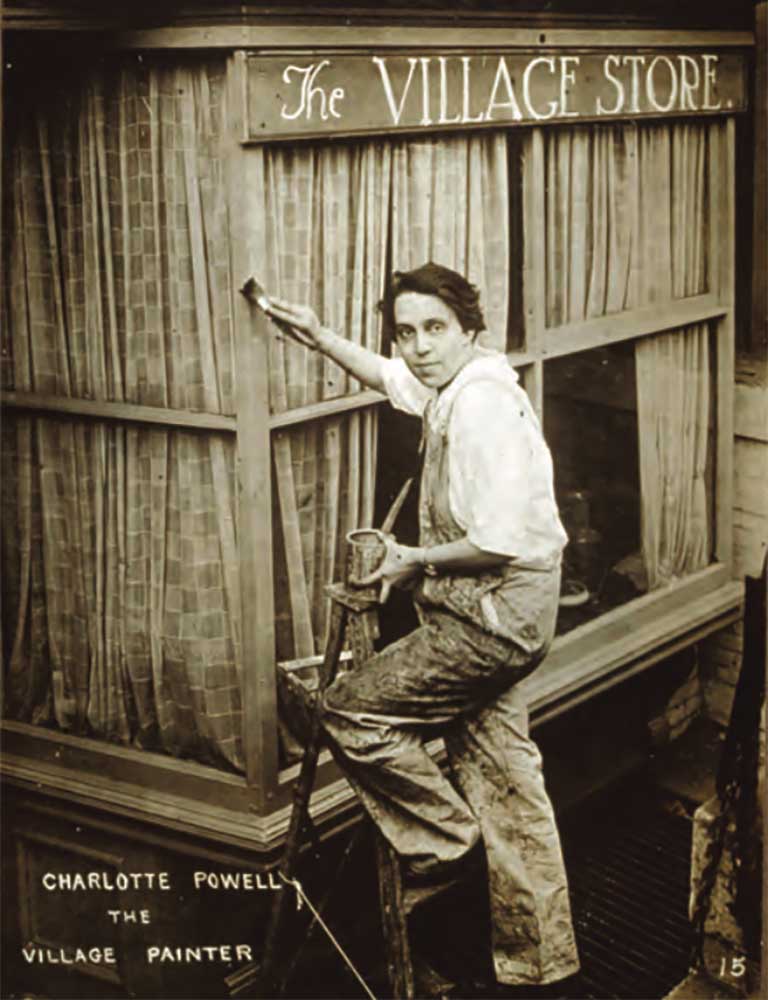

In openly endorsing free love, as well as in her pursuit of a career and an intellectual life outside the home, Parton identified herself as one of the “new women.” The Delineator encouraged popular reception to these avant-garde women by hiring them as professionals and publishing stories celebrating their lifestyle. Popular culture in the early 1900s became fascinated with “new women,” who challenged the gender stereotype and sex roles of the Victorian age. These women craved opportunities to participate independently of men in all aspects of society; to enjoy their sexuality without the restraints of convention; and to develop their talents in the arts, business, or politics. Many of the new women, such as Parton, accepted jobs and even built careers in philanthropy. But their priority was usually their own fulfillment, happiness, and expansion of opportunity. To them, sexual freedom, eco- nomic freedom, and political freedom were integrated parts of a full life. The new women tried to live their lives as expressions of those freedoms.

Certainly, the new woman expressed an early form of feminism. Though Century Magazine in the early 1900s claimed that the word was so new that it was not yet in the dictionary, “feminism” appeared poised to restructure social life in the United States by radically altering the attitudes of both men and women. Feminism was being hailed as a “world wide revolt against artificial barriers which laws and customs inter- pose between women and human freedom,” compared in importance to the Enlightenment and its progeny, democracy. The feminist movement at the turn of the century built upon the philosophical tradition of the Enlightenment in valuing individualism and assuring a private right of each woman to develop her natural potential in pursuit of her desires. As historian Nancy Cott notes in her 1987 book The Grounding of Modern Feminism, the “new Woman stood for self-development as contrasted to self-sacrifice or submergence in the family. Individualism for women had come of age” in the person of the new woman.

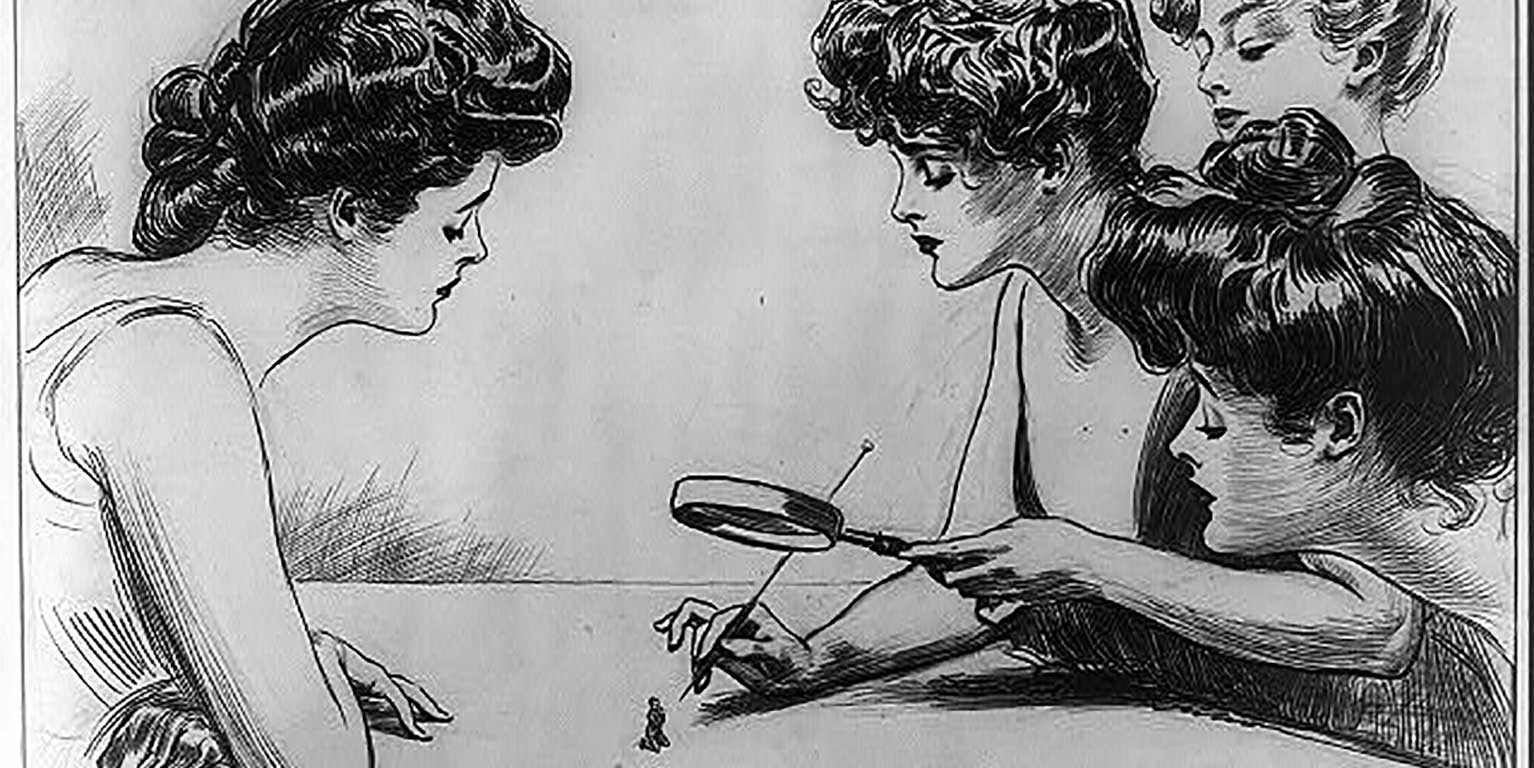

Gibson Girls

The complexity of the new woman was wonderfully captured by Charles Dana Gibson in his Gibson Girl cartoons. The Gibson Girl was intelligent, confident, and always in control in relations with men. Prominent author and reformer Charlotte Perkins Gilman saw in the Gibson Girl drawings a depiction of “the new woman ... a noble type, indeed ... honester [sic], braver, stronger, more healthful and skillful and able and free, more human in all ways.” Certainly, these women seemed more human in the open expression of their sexuality and their repudiation of Victorian mores. Political activist Emma Goldman spoke for thousands of single young women when she wrote:

“Can there be anything more outrageous than the idea that a healthy, grown woman, full of life and passion, must deny nature’s demand, must subdue her most intense craving, undermine her health and break her spirit, must stunt her vision, abstain from the depth and glory of sex experience until a ‘good’ man comes along to take her unto himself as a wife?”

Parton lived among other “new women” and others who were perceived as radicals in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village. Both Darrow and Dreiser made introductions that provided her a ready network of friends, all drawn from New York’s liberal and artistic communities, among them Eugene O’Neill, John Reed, Max Eastman, Emma Goldman, Ben Reitman, Hutchins Hapgood, and Mabel Dodge. Parton became a vital member of the Greenwich Village community soon after arriving in New York.

One author describes Greenwich Village before the Great War as a “kaleidoscopic bohemia” that promised a final “sweeping away of Victorian strictures.” Parton found a home in the Village, the center of a new feminist movement, where educated young single women, desirous of sexual freedom, careers, and a public voice, came together to express their demands for social change. Actresses, playwrights, and businesswomen, they sought a “single sexual standard for men and women” rooted in pleasure-gratification, which they hoped would replace “renunciation and regulation” as a basis for public morality. Parton enjoyed late night debates over wine and coffee, evenings with members of the Heterodoxy Club devoted to women’s rights, and weekends in Provincetown, Massachusetts, with her friend Gertrude Barnum. Romanticizing her involvement in the causes of the day, Parton noted: “We were like the early Christians. We just got together.” Generally, they all shared at least a minimal commitment to socialism. Her roommate, actress Ida Rauh, who would marry Max Eastman, once confronted a burglar in their apartment with an apology rather than a condemnation: “You wouldn’t have to do this for a living if we had a socialist revolution.”

Parton’s writings garnered attention from union leaders, politicians, and publishers. John S. Philipps, editor of the American Magazine, wrote to her: “That piece of yours in The Delineator was a beautiful thing. I wish we could have it for American Magazine—and I may tell you that it is only now and then that I feel envious of what I see in other magazines.”

Parton did not take long to develop her own writing style. She applied the pragmatists’ model of using inductive reasoning from emotional experiences to create truth. Parton found compelling stories of individuals suffering hardships from a strike, filthy living conditions in tenement housing, arduous working conditions in a mine, or children’s illnesses, without the resources to alleviate them. She used these vignettes to tell a broader story of poor or working people, hoping to create an emotional reaction, compelling readers to moral outrage and eventually to action. Union organizing issues became her passion and her stories were frequently published in labor newspapers and bulletins. Not only did she find real acclaim for the work she did, she also felt as though she was making a difference in people’s lives.

“Playboys and Girls”

As her fame and income increased, she saw her activism in different terms. After her marriage to Lemuel Parton, a syndicated columnist at the New York Sun, the couple bought a large apartment in Greenwich Village and made money through rents. Once they moved to the Palisades, Parton distanced herself from friends who desired a revolution and reconceived of her youth in Greenwich Village as “a stupid period” of her life: “Most of these people were wastrels. They wasted their talents in talk—and what’s become of them? So gay and so full of hope and so determined to save the world. We called ourselves intellectuals and radicals, and bohemians, but really we were playboys and girls.” While socialism may have lost some appeal to Parton, sexual freedom did not.

In the early 1900s, sex became a cultural, and even a political, concern as well as a personal one. Women not only argued for the right to vote, but also for other personal rights and freedoms. Well before the “flapper era” of the 1920s, sexuality made its way from Victorian bedrooms to the public consciousness. Magazines and films celebrated the openness of America’s interest in sex. Current Opinion reported that it was “sex o’clock” in the country; Good Housekeeping noted that the only way to control sexual desires is through satisfying them. As many young women flocked to large cities, those willing to exploit their natural charms found jobs as cocktail waitresses who earned cuts on each drink served to gentlemen patrons, or in environs offering more lurid sexual activities. Most of these new urbanites, however, found jobs as “shopgirls, clerks, and factory hands,” whose small wages made them vulnerable to men with money who blurred the already “fine line between courtship and promiscuity.”

In what seemed to many a highly charged sexual environment, the number of unwanted pregnancies increased, and thousands of women turned to unsafe practitioners who took not only the women’s money, but sometimes their lives as well, in performing illegal abortions. Margaret Sanger headed a widespread campaign for the legalization of contraceptives. She coined the phrase “birth control” and argued for women’s freedom to enjoy sex without the worry of unwanted pregnancies, although her later work and support of eugenics indicated that her endorsement of birth control had racist origins, at least in part. Yet Americans divided sharply over the openness of sexual discussions. Parton openly supported Sanger and witnessed her arrest for merely addressing contraception in public.

Parton saw herself serving on the front lines of the battle for sexual freedom and female social opportunity, in both her personal and professional lives, an emblem of her time. But she also believed that women were not doing enough to help themselves, succumbing to the comforts that men provided for women to keep them in their place. She argued women had “to understand the value of suffering and that women have not suffered enough; that they are too lazy, cat-like, love the couch, the cozy corner.” Women, she believed, would not be moved to fight for their rights so long as their subjugation remained comfortable.

Mark McGarvie

Mark McGarvie's (Ph.D. '00, History) academic interests and specialties are the intellectual and legal history of the United States, focusing on the legal delineation of private and public sectors, specifically as it relates to the construction of civil society, ideas and practices regarding philanthropy, and the separation of church and state. Current research and writing projects include a prospective law review article highlighting the influences of Thomas Jefferson upon the jurisprudence of Justice William O. Douglas and two books. The first, an edited volume, reconsiders the judicial treatment of the Second Amendment based on Douglas’s jurisprudential arguments regarding that text. The second is a microhistory using the life of Daniel Burnham to access the progressive movement and politics in Chicago in the early 1900s. Currently serving as Scholar-in-Residence at the Newberry Library in Chicago, McGarvie is also the author of The Pragmatic Ideal: Mary Field Parton and the Pursuit of a Progressive Society (Cornell University Press, 2022).