'What Took You So Long?'

Although Mays and his future wife, Rose, knew one another as children, it took several years—and some unfortunate circumstances—before they dated. (The pair eventually married and had two daughters, Heather and Kristin.) “We really didn't connect until his dad passed when [Bill] was in college,” Rose Mays says. “He was in his second year at IU and he came home to help his mom after his dad's death. . . . During that time, he went to the University of Evansville where I was a student.”

By 1965, Mays returned to IU. At the time, there were no Black faculty members and only two other Black students in the chemistry department. As for Black entrepreneurial role models in the field of chemistry? Mays came up empty.

Nevertheless, he'd complete his business training at IU and land positions with multiple Fortune 500 companies. “It's kind of this whole one degree of separation from IU,” Mays-Corbitt notes. “IU allowed him to get the practical and technical training through the School of Chemistry, the business training through the Kelley School of Business, an internship with Procter & Gamble, and then the subsequent role with Cummins through the career center.”

Mays worked briefly as a test chemist before moving to sales with Procter & Gamble. “That's really when he figured out what his best skills were and what he was happy at,” Rose Mays says. “Bill was really a people person. He was able to talk to people of all levels.”

In 1973, Mays was named assistant to the president of Cummins Engine Company. Just four years later, he became president of Specialty Chemicals. During his tenure there, sales jumped from $300,000 to over $5 million. But Mays had reservations about the company. “To be called a 'minority-owned' or 'minority-controlled' company, a minority needed to have some type of control [on the board,] Mays-Corbitt says. “And neither he nor any other minority was given access to make decisions at a board level. He was just very frustrated by that aspect.”

She continues, “Integrity is one of the wonderful traits that I always saw in my dad growing up. . . . Although no one was watching how this company was made up and how decisions were being made, I don't think [the board issue] sat well with him. . . . He came home and told [my mom] he was going to resign and start his own company, and she looked at him for about 30 seconds and said, 'Well, OK. What took you so long?'”

It was the beginning of Mays Chemical. Within its first decade, the company would reach $50 million in sales. By 1995, that number would double. By 2008, it would more than double again. Clearly, he'd found a workable formula for entrepreneurial success. As Mays told his granddaughter, Ashley Scurlock, during a 2012 StoryCorps interview, “Education, experience, access to. . . capital, and the ability to attract and retain good employees. If you [have] those things, then you have an excellent chance of getting and running a successful business.”

Greater Influence

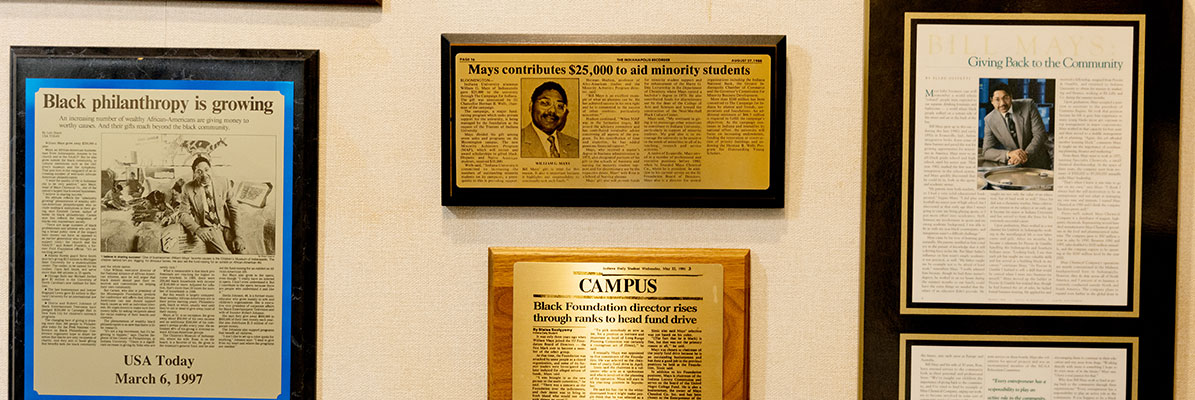

During his career, Mays pursued several side ventures which, at first glance, may have seemed somewhat disparate. For instance, in 1990, he purchased The Indianapolis Recorder newspaper. And, a few years later, he acquired television and radio stations which he eventually sold to Radio One for $40 million. As Mays told Scarpino, “People say, 'You run a chemical company. What do you know about media?' I don’t know a lot about media, but I do know the people who have been successful understand that you’ve got to control that just like you’ve got to have some impact on politics.”

Mays's media acquisitions partly were prompted by an exchange he'd had with fellow Kappa Alpha Psi member Percy Sutton. The famed Civil Rights advocate, politician, and business leader co-founded the Inner City Broadcasting Corporation. Mays recounted, “I said [to Sutton], 'Why? Why would you want to [run Inner City Broadcasting]? Politically you’re so successful and you’ve got wealth outside of that.' He says, 'Well, because one of the things that Black folks have to be able to do is control the media, because—or certainly influence the media,' he says. 'Because the media is what generates the images—the negatives—and if you can’t get your story out, you have no way of counteracting major publications.'”

Still, Mays took pains not to be overly controlling with his media holdings. “He was very clear that he did not want to dictate what went into the [Indianapolis Recorder],” Rose Mays says. “But, every once in a while, he did write an editorial or two on an issue.”

Mays's other investments—including golf courses, construction companies, and more—had at least one thing in common. As Marshall explains, “Bill would say, 'It's all about access. You don't have to necessarily take advantage of everything that comes your way, but at least be in a position to make that decision yourself.' So, most of the things that he did entrepreneurially were about creating channels of access for people to excel.”